While Emma has been translated into languages such as French as early as 1816, it wasn’t until the 20th century that we find publications of this novel in Spanish.1 The first of Austen’s novels to make their Spanish debut on the market was Persuasion, translated and published in Spanish in 1919. It wasn’t until after the Spanish Civil War that Emma caught the attention of a translator and publisher.2 The first Spanish translation of the novel, published in 1945, can in fact be found in our own Goucher College Jane Austen Collection. This translation by Jaime Bofill Y Ferro was donated in 1998 by Barbara Winn Adams along with more than 275 volumes in the Winn Family Collection.3

Each translation and work on display in this exhibition can be found in Goucher College’s Jane Austen Collection and has found a home in Goucher College’s Special Collections & Archives. If you are new to this stunning and extensive collection, I want to take a moment to introduce you to what lies within our very own library’s walls.

The Jane Austen Collection at Goucher College collection began with the bequest of Alberta Hirshheimer Burke, a 1928 graduate of the college. Burke began buying rare Austen editions and manuscripts in the 1930s after a trip to England. Quickly becoming adept at the book trade, Burke began following the market on Jane Austen materials. Over time she built a distinguished private collection of Austen books and manuscripts. Upon Burke’s death in 1975 and in accordance with her will, her collection was divided between Goucher College and the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. Goucher College received more than a thousand early editions and books as well as personal correspondence.

Jane Austen Collection at Goucher College

Thanks to Alberta Burke’s and the Winn family’s donations and Goucher College’s continued efforts to grow their Jane Austen Collection, we are able to explore the world of Austen translations in this exhibition and spotlight the creative individuals who worked on them. While not all literary translators are credited for their work or known outside of their contribution to a literary translation, we are fortunate to know about the lives of two of the Spanish translators on display in this exhibition. It was very important to me when I embarked on this project that the translators so often hidden in the shadows of the original author have a moment in the spotlight. Without them, Emma would not have been accessible to many Spanish-speaking readers and this exhibition would not be possible today.

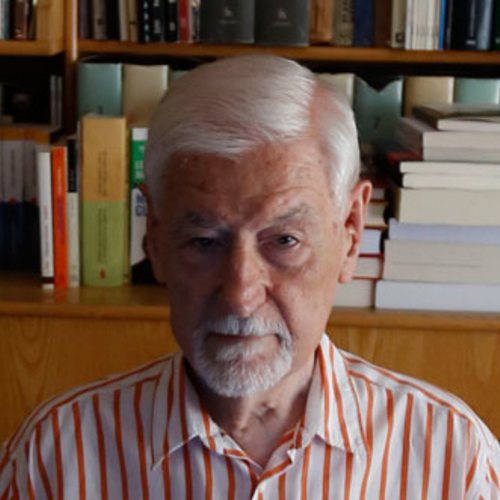

José Luis López Muñoz

José Luis López Muñoz is the translator for the 1971 Spanish edition of Emma, displayed in this exhibition; however, this is not the only Austen translation he worked on. He also translated the 2013 Spanish translation of Sense and Sensibility and the 1997 Spanish translation of Pride and Prejudice. López Muñoz is a renowned translator with a translation career spanning over half a century. His Sense and Sensibility translation won him ACE Traductores’s 2014 Esther Benitez award for the best translation published in Spain.4

López Muñoz has stated that “the essence of translation” is “a consequence of desire, of the will to make known, to communicate something, even if it is not our own.” In his opinion, “the literary translator has to be a writer or, rather, he has to like writing and has to have a love for language and written language.” If there is a principle that guides the exercise of it, it is that, “having made the first version of a text, then you have to distance yourself,” since “the translated text has to be autonomous, without references to the original.

Diccionario Historíco de la Traducción en España (Translated from Spanish to English by Google)5

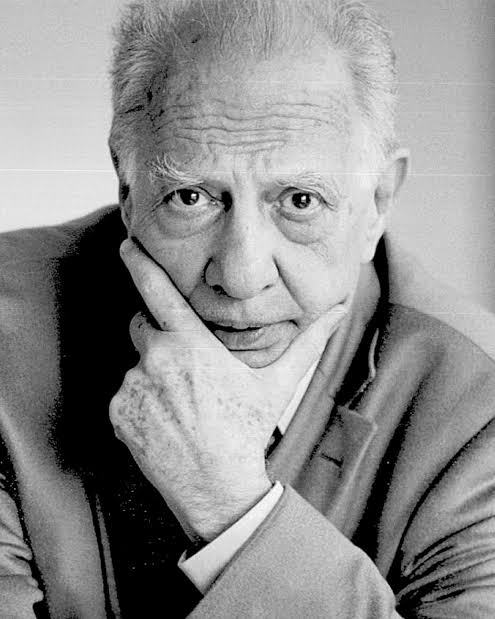

Sergio Pitol

Sergio Pitol translated Emma into Spanish in 1972; his translation is reprinted in the 2014 Spanish edition of Emma on display in this exhibition. Pitol, who passed away in 2018, was a prominent Mexican writer as well as a prominent literary translator, translating into Spanish over 50 works of British, Eastern European, Russian, and Italian literature.6

The fundamental objective of writing was to discover or intuit the ‘genius of language’, the possibility of modulating it at will, of turning a word repeated a thousand times into new ones simply by arranging it in the appropriate position in a sentence… I read Alejo Carpentier. What attracted me to the Cuban writer was the rhythm, the austere melody of his phrasing, an intense verbal music with classical resonances and modulations from other languages and other literatures.

Excerpts from Sergio Pitol’s Cervantes Prize Speech. (Translated from Spanish to English by Google)7

Continue exploring the exhibition and enter the visual world of each cover.

Referenced Resources:

- Dow, Gillian. “Translations.” The Cambridge Companion to ‘Emma,’ edited by Peter Sabor, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 166-185. ↩︎

- Romero Sánchez, Mari Carmen. “A la Señorita Austen: An Overview of Spanish Adaptations.” Persuasions, vol. 28, no. 2, 2008. ↩︎

- Kaplan, Laurie, and Nancy Magnuson. Twenty-Five Years of Jane Austen. 2000. ↩︎

- García Soria, Cinthia. “Judgement and Feelings: Sense and Sensibility‘s Journey to the Spanish-Speaking World.” Persuasions, vol. 43, no. 1, 2022. ↩︎

- Pegenaute, Luis. “López Muñoz, José Luis.” Diccionario Historíco de la Traducción en España, Accessed 5 Dec. 2023. ↩︎

- Sánchez Prado, Ignacio M. “Literature as Life: Sergio Pitol’s ‘Trilogy of Memory.’” Las Angeles Review of Books, 28 July 2017. ↩︎

- Manrique Sabogal, Winston. “Sergio Pitol, the Nomadic Mexican Writer of Life and Literary Genres, Dies.” WMagazín, 12 Apr. 2018. ↩︎