Emma Across Academia

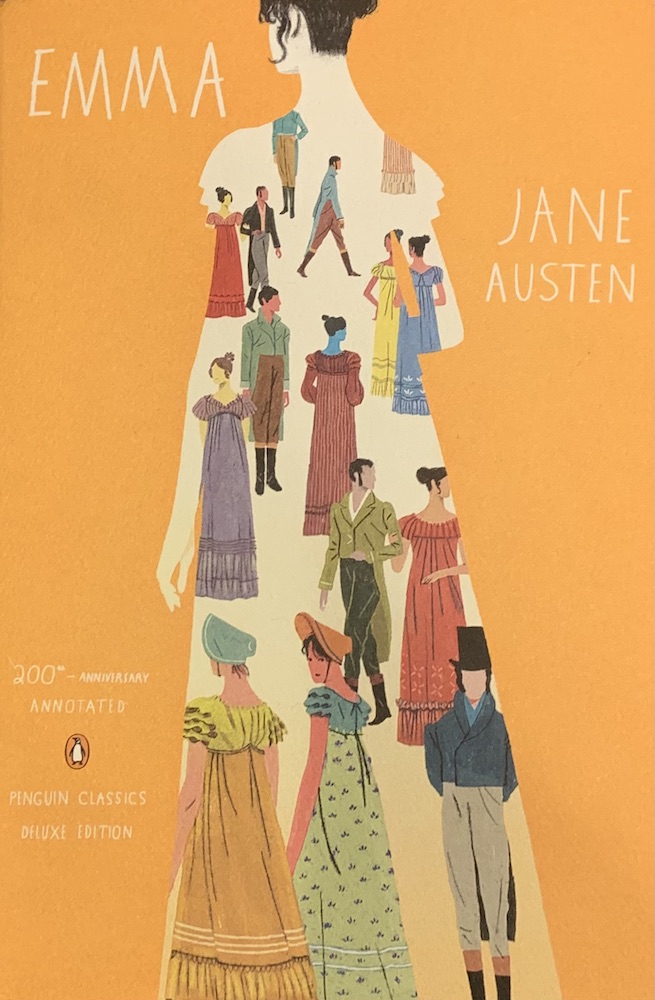

Emma. Jane Austen. 200th-anniversary annotated edition, introduction by Juliette Wells, cover art by Dadu Shin. Penguin Classics, 2015.

Elda Rotor, then Associate Publisher & Editorial Director of Penguin Classics, approached me in 2014 with a very appealing project: to invent a new kind of edition of Emma that would especially welcome first-time and nonacademic readers. Instead of endnotes, which many readers—including my students—find off-putting, I wrote short “Contextual Essays.” My plot-spoiler-free introduction explains how Emma fits into Austen’s career and what its earliest readers thought of it.

available for checkout from the Main Collection, Goucher College Library

–Juliette Wells

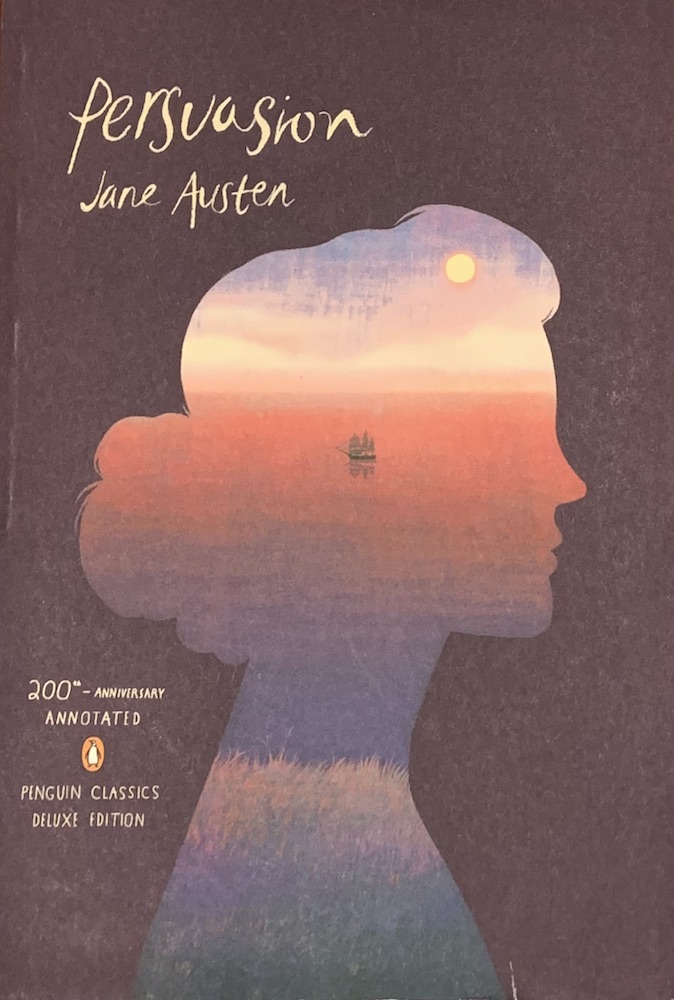

Persuasion. Jane Austen. 200th-anniversary annotated edition, introduction by Juliette Wells, cover art by Dadu Shin. Penguin Classics, 2017.

I love the cover images that Brooklyn-based artist Dadu Shin created for both my Penguin Classics editions. Years before Bridgerton featured actors of color playing Regency characters, Shin’s Emma cover invited us all into Austen’s world. For Persuasion, he pairs Anne Elliot, dreaming of her beloved at sea, with Captain Wentworth, dreaming of her on land. I’m proud that both these editions help spread the word about Goucher’s Jane Austen Collection, by including reproductions of illustrations from volumes once owned by Alberta Burke.

available for checkout from the Main Collection, Goucher College Library

–Juliette Wells

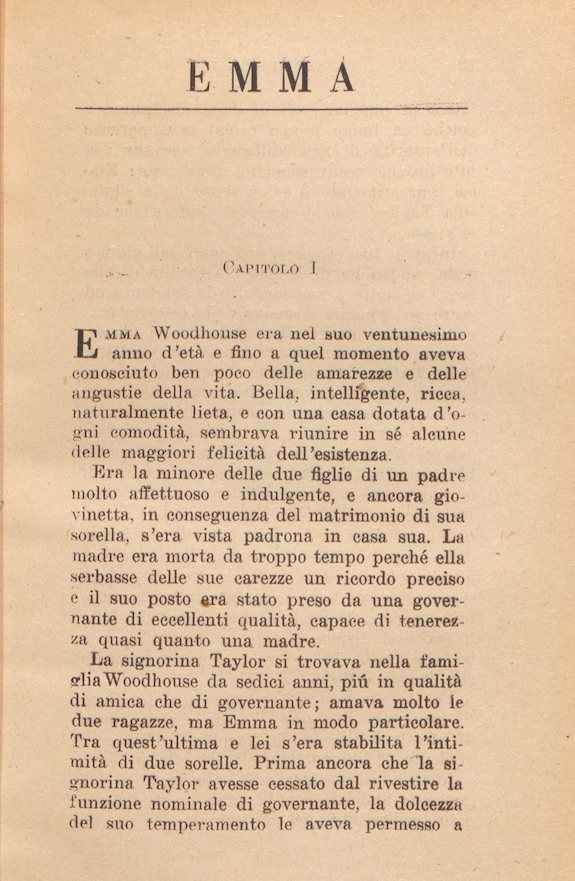

Italian Translations by Lena Brazfield

“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.”

–Emma, Chapter 1

Each of these translations takes an incredibly different approach to capturing the immortal first sentence of Emma. The translators all undertake an amount of restructuring, but differ greatly in how they convey that Emma has had “very little to distress or vex her.” The 1945 copy roughly says that she has not known the bitterness or anguish of life, while both sentiments within the 1959 version are synonyms for pain. The 1979 translation conveys that she has known little sadness or opposition. All of these interpretations of the first line carry truth about Emma’s character moving forward in the novel but the implications of each are very different. This is just one example of how translators carry massive responsibility for how readers end up experiencing works of literature.

Images and books from Alberta H. and Henry G. Burke, Jane Austen Collection, Special Collections & Archives, PR4034 .E5 F6 1945, PR4034 .E5 I7 1959, and PR4034 .E5 I7 1979, Goucher College Library

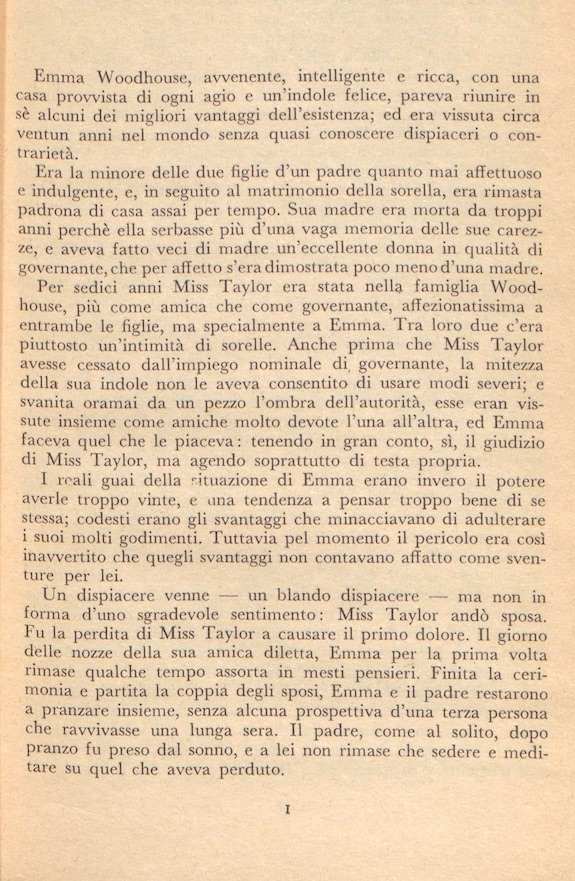

Time to be in Earnest. P.D. James. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

This autobiography by the British detective novelist P.D. James’ life includes a speech given by James at a Jane Austen Society (UK) Annual General Meeting titled, “Emma Considered as a Detective Story.” James claims that Emma is one of the earliest examples of the detective novel with many mysteries woven throughout its text. But the main mystery lies within the story of a side character, Jane Fairfax . . .

from the teaching collection of Prof. Juliette Wells

–Lilia Gestson ’24

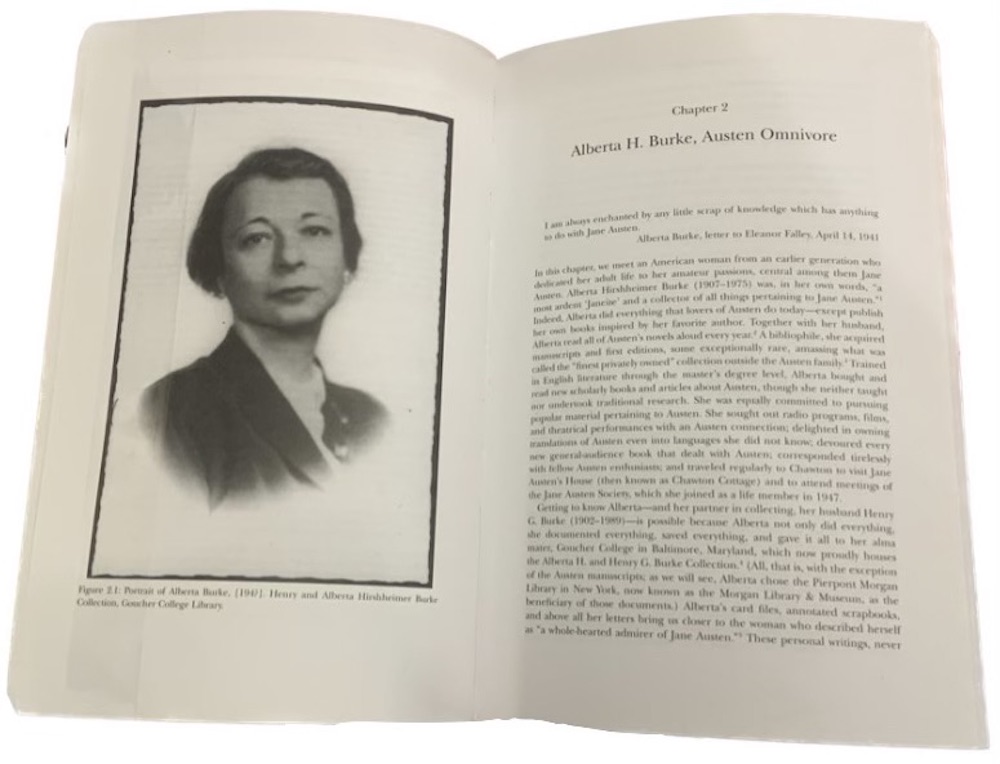

Kate Dannals. “Alberta Hirshheimer Burke, As Best I Understand Her.” Independent work funded by the Brooke and Carol Peirce Center for Undergraduate Research in Special Collections Fellowship, 2009.

I was a psychology major and conducted my research as an independent study through the psychology department. In my junior year, I took a course in qualitative research methods and I wanted to combine those skills with my love for archival work. Working with Mrs. Burke’s letters and other ephemeral materials gave me the opportunity to do just that.

Naively, I viewed Mrs. Burke as just another wealthy, privileged, materialistic woman who indulged her interest in Jane Austen to an extreme and then left us to deal with her multitude of stuff. However, in reading and re-reading her words, I found a new appreciation for Alberta Burke, her devoted husband Henry, and their astounding collection of Austen treasures. After transcribing some of the letters, I used a coding technique that I’d learned in my research methods class and combed through the text to construct a personality sketch of Mrs. Burke, a copy of which is now on file in the archives. Currently I am three days away from having my master’s degree in clinical psychology.

Archival work will not be my first career, though I continue to work in special collections as a way to balance my clinical endeavors. Nevertheless, I do believe my exploration of Mrs. Burke will help me to be a better clinician. She reaffirmed for me that first impressions, though informative, are not always correct. I have never known or studied someone like her before — a true aesthete and bibliophile; a privileged introvert whose friends were novels, frescoes, and cats; and a meticulous Janeite who managed to turn her obsessive nature into a functional lifestyle and rich legacy.

from Special Collections & Archives, Goucher College Library

–December 29, 2011 post by Kate Dannals

Collecting Austen by Nicole Mead ’23

“I think all collections, particularly book collections, are necessarily love stories.”

–Henry G. Burke, speaking to the Baltimore Bibliophiles, 1976

Janeites (Jane Austen fans) demonstrate their dedication to Jane Austen through numerous avenues of expression, such as art, pottery, fanfiction, and collecting. Collecting is an activity with its own set of complicated historical and social implications. Our understanding of what it means to be a collector continues to evolve throughout the years – from the 1800s, when a book collector might be considered a “bibliomaniac” (a pseudo-psychological illness); to 2009, when the TLC television program Hoarders was first released, and all the way to 2019, when Marie Kondo’s Netflix show sparked a new wave of distaste for people with an accumulation of material goods. Mainstream perception of collectors has been subject to change, but also to stigma in both societal and psychological realms. There is no single answer as to why people collect, but examining the different reasons for collecting across different psychological perspectives will yield several different answers to our question. One could take a psychoanalytical approach, which might assume a person is collecting to gain a sense of control related to past trauma, or an existentialist approach, which assumes we collect to feel a sense of immortality.✻✦

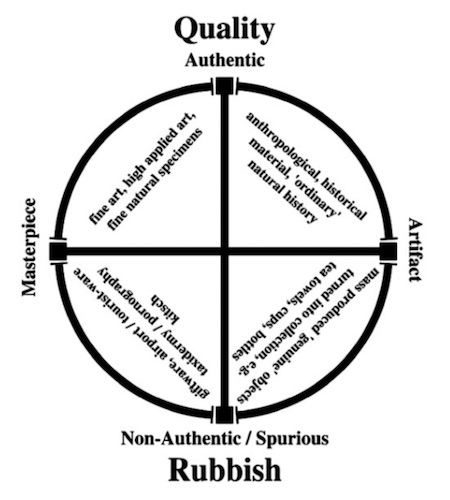

Another psychological approach would be to examine collecting behavior solely from a medicalized perspective; a person would be tasked with differentiating between collecting and hoarding disorder. Many are familiar with the idea of hoarders. It became an official diagnosis in the DSM-5 (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) three years after becoming widely recognized through the television show “Hoarders.” The inclusion of hoarding disorder in the DSM-5 was marked by concerns about its inability to distinguish from normative collecting behavior. There are a few distinctions between collecting and hoarding that are worth noting. One is the perceived versus actual value a collector and a non-collector assigns to items hoarded in their collection. ♥ The “Axes of Value” (see figure) can be a useful visual when examining the actual versus perceived value of a person’s object in their collection.

Beyond simply understanding the value of a person’s collection, it is immensely important to look at how a collection (1) makes them feel, (2) affects their well being, and (3) affects their quality of life. I wanted to take the opportunity to honor alumna Alberta Burke, the reason Goucher College is lucky enough to have our esteemed Austen collection. Alberta Burke’s affection for and dedication to all things Jane Austen led her to possessing the “finest privately-owned” collection outside the Austen family.✿ Burke is a bit of a mysterious figure; she was private, and seemingly shy.✿ Her passion for collecting did not stem from a desire for status or wealth, or a desire to accumulate material goods. Instead, her collection was rooted in her affection for Austen and a desire to be closer to her.✿

Though I am not qualified or inclined to assess the nature of Burke’s collecting, I can note that among the primary negative effects of collecting behavior, such as isolation and risk-taking behavior, Burke displayed few signs of these behaviors.✦♥✿ In Burke’s lifetime, her collecting allowed her to gain community and connection within the Janeites, and she maintained a strict budget. It seems, by all accounts, her collection seemed to reap mostly positive benefits for her mental well-being. Burke experienced satisfaction from meeting and setting collecting goals, gained expertise/competence, and relatedness.✦♥ Beyond that, her collection and her generosity continues to benefit Austen lovers, as most of her collection is available to all Goucher students, here at the Goucher Library.

“I have bought each thing because I felt I could not live without it, and because Jane Austen is ‘St. Jane’ in my private hagiology.”

–Alberta H. Burke, letter to Percy Muir, 1948

✿ Wells, Juliette. “Alberta H. Burke, Austen Omnivore.” Everybody’s Jane: Austen in the Popular Imagination. Bloomsbury Academic, 2011, pp. 35-59.

✻ McKinley, Mark B. The Psychology of Collecting.

✦ McIntosh, William D., & Schmeichel, Brandon. “Collectors and Collecting: A Social Psychological Perspective.” Journal of Leisure Science, vol. 26, no. 1, 2004, pp. 85-97.

♥ Nordsletten, Ashley E., & Mataix-Cols, D. “Hoarding versus collecting: Where does pathology diverge from play?” Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 32, no. 3, 2012, pp. 165-176.

Juliette Wells. Everybody’s Jane: Austen in the Popular Imagination. Bloomsbury Academic, 2011.

The public’s fascination with Jane Austen continues to create a new generation of Austen fans, and with that, new fan art, collections, and discourse surrounding the renowned author. This book provides insight into Austen’s popularity, as well as exploring the world of two important figures in the Austen and Goucher literary community: Austen fans and collectors Alberta and Henry Burke. The book provides an unprecedented amount of information on Alberta Burke, about whom little was previously known.

available for checkout from the Main Collection, Goucher College Library

–Nicole Mead ’23

Juliette Wells. Reading Austen in America. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Drawing on original archival research, I offer an extended portrait of the original owner of Goucher’s copy of the 1816 Philadelphia Emma: Christian, Countess of Dalhousie, a Scotswoman living in British North America. My final chapter offers an account of Alberta H. Burke’s learned correspondence with an aspiring English bibliographer, both sides of which are held in Special Collections and Archives.

available for checkout from the Main Collection, Goucher College Library

–Juliette Wells

Harriet Smith Through Time by Molly King ’23

Something notable about Jane Austen’s writing is the lack of detailed physical descriptors of her characters. The first part of Emma’s immortal opening line, “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever and rich,” is almost the closest Austen gets to describing Emma’s features, though a few more details emerge throughout the novel, including her hazel eyes. Austen describes Harriet Smith in more detail: Emma sees her as “a very pretty girl, [whose] beauty happened to be of a sort which Emma particularly admired. She was short, plump, and fair, with a fine bloom, blue eyes, light hair, regular features, and a look of great sweetness” (chapter 3). Even in this narration, there is a vagueness that allows the artists of illustrated editions many options in how they depict both Harriet and Emma.

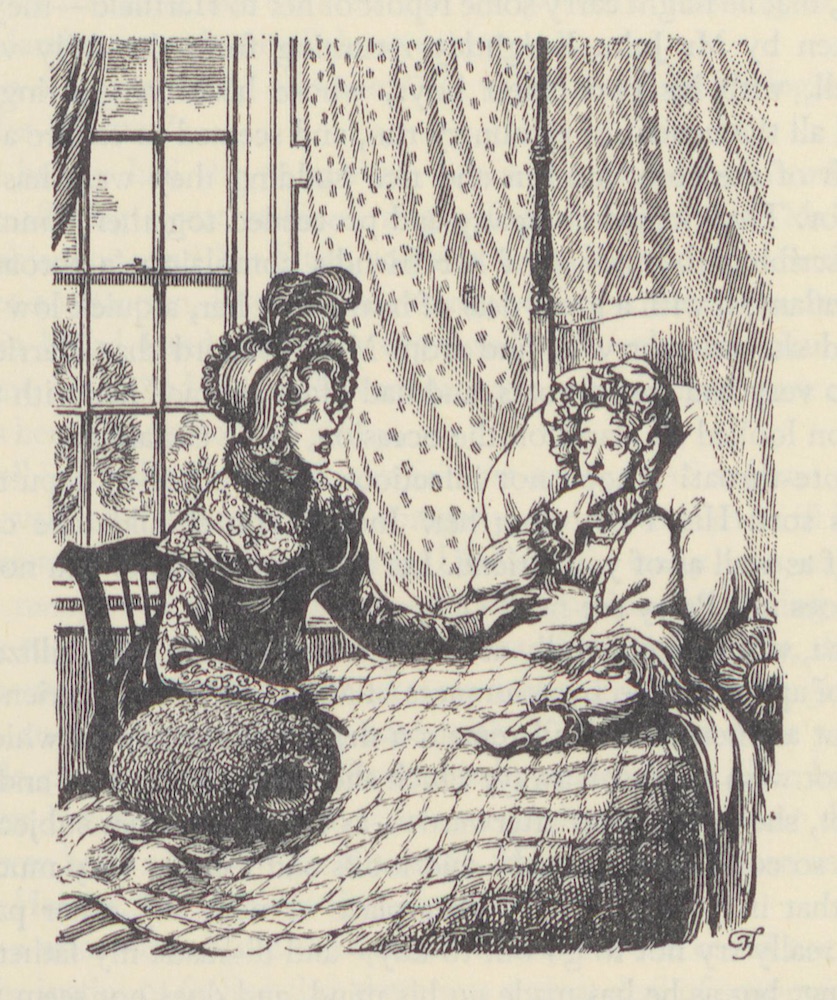

Engraving of Emma and Harriet. Jane Austen, Emma, illustrated by Joan Hassall, published by Folio Society, 1975.

This engraving depicts Emma Woodhouse sitting beside an ill Harriet Smith as Harriet clutches the sermons she transcribed for Mr. Elton. Harriet is looking rather poorly, not only from a fever and sore throat, but in devastation over not being able to attend the Westons’ Christmas dinner where Mr. Elton will be in attendance.

Image from Alberta H. and Henry G. Burke Jane Austen Collection, Special Collections & Archives, Goucher College Library

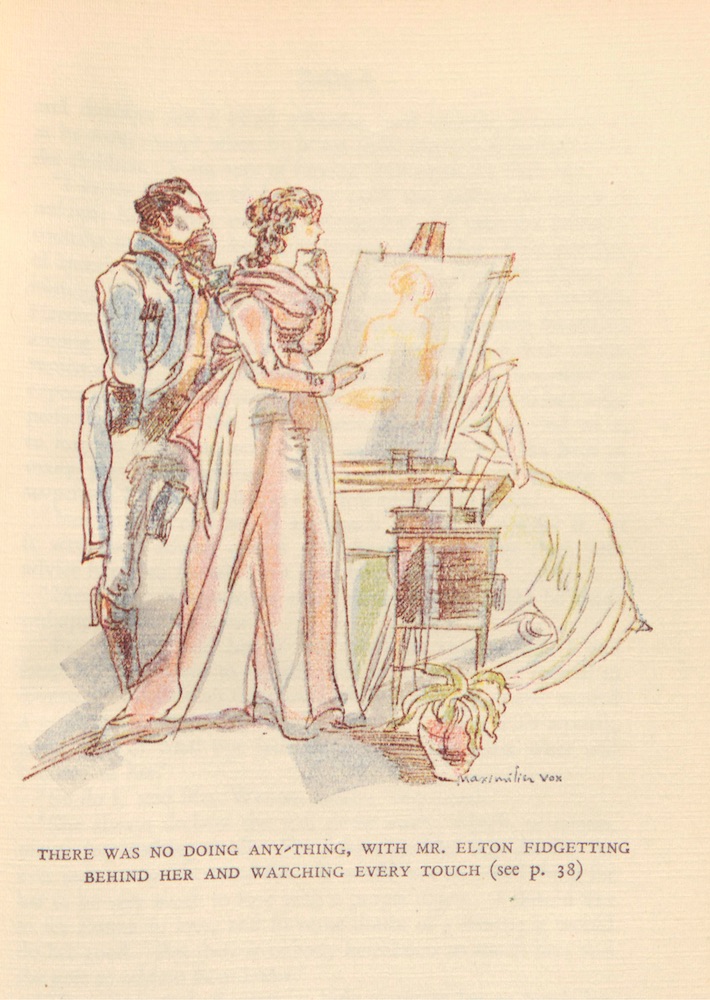

Illustration of Mr. Elton and Emma. Jane Austen, Emma, illustrated by Maximilian Vox, 1934.

This illustration, unique amongst its companions of display for its coloration, depicts Mr. Elton standing behind Emma as she takes Harriet’s portrait, with Harriet sitting behind the easel. It is worth noting that Harriet, a woman whose class status is uncertain at this point in the story, does not have her likeness illustrated but rather a likeness of her likeness.

Image from Alberta H. and Henry G. Burke Jane Austen Collection, Special Collections & Archives, Goucher College Library

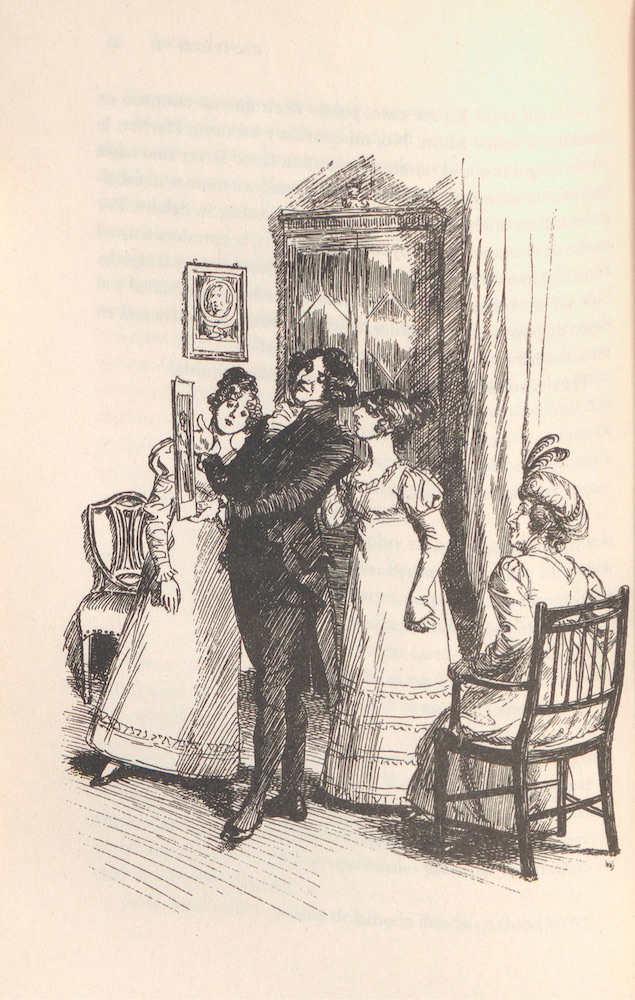

Illustration of Emma, Harriet, Mr. Elton, and Mrs. Weston by Hugh Thomson (1896). Reprinted in Jane Austen, Emma, translated by Sergio Pitol, 2013.

This illustration depicts Mr. Elton admiring the portrait that Emma created of Harriet. It is uncertain which woman is which, as it stands to reason that Mr. Elton would be showing Emma’s drawing to Harriet, and Harriet, having an interest in Mr. Elton, might be comfortable placing a hand on Mr. Elton’s arm. Consequently, given his feelings towards Emma, he might be leaning towards her as a way of getting close to her without abandoning propriety. Mrs. Weston is present as well, sitting off to the side. Mr. Elton’s stance could also be indicative of ignoring Harriet, whose social class is still uncertain, in favor of showing the portrait to Emma and Mrs. Weston, the two landed ladies.

Image from Jane Austen Collection, Special Collections & Archives, Goucher College Library, Goucher College

Juliette Wells. “Intimate Portraiture and the Accomplished Woman Artist in Emma.” Art and Artifact in Austen, ed. Anna Battigelli. University of Delaware Press, 2020.

First presented as a paper at the 2017 “Jane Austen & the Arts” conference at SUNY Plattsburgh, this essay approaches Emma’s creation of Harriet Smith’s likeness as an example of two contradictory artistic categories: intimate portraiture, in which a professional artist produces an image for private viewing, and feminine accomplishments, which were considered harmless ways for gentlewomen to pass the time—as well as opportunities to compete with each other for masculine attention.

available for checkout from the Main Collection, Goucher College Library

–Juliette Wells

Juliette Wells. A New Jane Austen: How Americans Brought Us the World’s Greatest Novelist. Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.

In my latest groundbreaking study, I show that Austen’s global reputation was established not by British scholars, as is commonly believed, but by visionary American writers and collectors, working largely outside academia. Making use of newly available sources, I weave together colorful, compelling cases studies of men and women—including Alberta H. Burke—who, from the 1880s to the 1980s, helped readers appreciate Austen’s novels, persuasively advocated for her place in the literary canon, and preserved artifacts vital to her legacy.

available for pre-order

–Juliette Wells